The UN can't solve Myanmar's problems

What the people of Myanmar want today is something that the deeply traditionalist, unimaginative and slow-moving UN system cannot provide any meaningful support to.

On 31 January, a short clip of an interview with the UN Special Envoy to Myanmar, Dr Noeleen Heyzer, tweeted by Channel News Asia correspondent, May Wong, triggered a major outrage in Myanmar. In the clip, Dr Heyzer is seen proposing some solutions to the post-coup crisis in the country, most of which are based on a broad call for a multi-stakeholder, non-military led political dialogue between all parties.

One particular proposition – regarding a possible “power sharing” arrangement – angered people. She said:

“I know that many young people – especially the young – they’re willing to die fighting for a total political transformation. Any political transformation requires a process, and its not going to happen overnight. And therefore, I want them to have something to live for, not to die for. And they need to negotiate what this power sharing could look like over a long term. And they have to be at the table…”

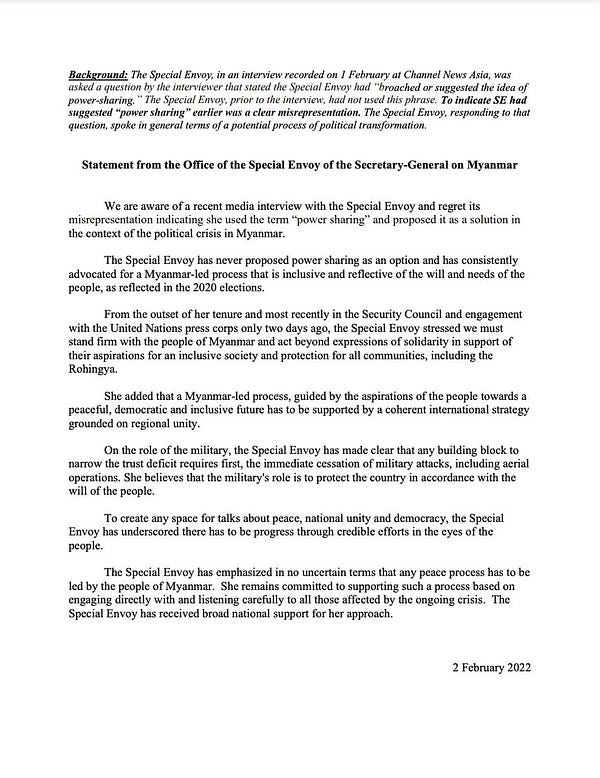

Realising that the Special Envoy had stepped on to a slippery slope (and probably spoken beyond her brief), her office later issued a media statement claiming that her comments were “misrepresented” and that she never proposed power-sharing “as a solution”.

However, given the existence of clear video evidence to the contrary, the statement has backfired on Dr Heyzer who is now being accused of lying to the people of Myanmar. More than 240 civil society organisations, including the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) and Justice For Myanmar (JFM), have called for her immediate resignation.

Subsequently, in a text interview with DVB, she expressed regret and apologised for engaging on the question of “power sharing”, stressing that she never used the term “power-sharing” in her capacity as Special Envoy (once again, the video shows otherwise).

Dr Heyzer’s proposals, as naive and irresponsible as they might sound to someone from Myanmar or those who are closely familiar with the exact nature of the current situation, are unsurprising and very typical of the UN’s approach to peacemaking. They flow from a textbook and rather, orthodox vision of peace – perfected over the Cold War period and later adapted to a deeply neoliberal framework of “resolving” conflicts through multi-stakeholder dialogues. More often than not, this kind of peace-brokering privileges stability over justice and economics over politics.

Various scholars have criticised the UN’s standard peacemaking approach for different reasons. One of these is that UN-led peace agreements often end up “reproducing the very sources of violent conflicts” that they seek to destroy. Others have accused the UN of applying a “one-size-fits-all” approach to brokering peace in different contexts. One can see clear shades of these tendencies in Dr Heyzer’s approach, which seems to be ignorant of Myanmar’s endemic power structures.

Any political dialogue in Myanmar under the current framework (doesn’t matter who brokers it or how ‘equal’ it is) will ultimately end up empowering the already-powerful military, which remains the primary source of violence in the country today. This is because of the extraordinary political, economic and military capital that the Generals have accrued over the past decades through the use of non-political means (read: brute force and intimidation). This entrenched power continues to be duly legitimised by the 2008 military-drafted constitution, which gives the Generals a literal veto power over Myanmar’s “democracy”.

Even without the 2008 constitution, the military has other ways to drive a knife into Burmese politics and twist it however it wants to secure favourable outcomes. For instance, it can use ceasefire regimes, such as the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), to tame ethnic aspirations and the politics of federalism. If all else fails, it can just use some good ol’ brute force to suppress democratic yearnings and mix it with some fuzzy talk about unity, peace and progress. In essence, the political economy of Myanmar remains heavily tilted in favour of the boys with the big guns and big money.

Further, recent history is replete with clear evidence of how untrustworthy the military can be when it comes to “dialogue”. This Twitter thread by independent researcher, Kim Jolliffe, takes a deep-dive into how the Generals have used the illusion of dialogue to deceive Myanmar’s political actors time and again:

These critical power dynamics and historical context are completely missing from the Special Envoy’s propositions. There is no talk of pushing the military out of politics by, say, abolishing the 2008 constitution and initiating a new constitution-drafting process. And to be honest, it would be naive to expect a UN Special Envoy to talk about getting rid of a country’s constitution or an entire institution – it is simply too radical a proposal for a global neoliberal institution like the UN.

The UN, after all, is not an agent of people’s revolution. It is not made up of people who would bring down the Bastille or run out into the streets with pitchforks. In fact, quite the opposite – it is a bureaucratic body created by states to “manage” or delay popular movements against entrenched authority. It is an institution that sees “peace” as a moral virtue and considers all violence as bad, unnecessary or apolitical. That is why Dr Heyzer so confidently said that a “total political transformation [in Myanmar] won’t happen overnight” and needs a “process”. Sure, a radical political change definitely won’t happen overnight, but there is absolutely no guarantee that a “process” could ensure that sort of change. In fact, one could argue that such a “process” in the prevailing context would squarely maintain the status quo or some distorted version of it.

A truly fair dialogue can only take place between two equals. And at the moment, the “two sides” in Myanmar (if there are only two sides, that is) are not equal by any means. In fact, the only “process” that is infusing some parity into the equation is the armed revolution. By directly challenging the military’s firepower and strategic dominance over Myanmar (especially the Bamar heartland) and denying the junta effective administrative control over territories, the armed revolution is attempting to dilute the entrenched power and relative advantage that the Generals so far enjoyed. It is forcing the military into a position of weakness so that when it comes to the table next (if it gets to that stage in the future that is), it can’t take the other parties for granted like it has till now. Viewed from the other end of the line, it is arming the relatively disadvantaged political actors with sufficient leverage to force the Generals to crawl back to their barracks.

In my view, the solution to Myanmar’s ordeal will only come from within. Yes, it will receive limited support from some important regional and international actors (like ASEAN, US, India), but ultimately, it is the people of Myanmar who will decide what needs to be done with the military. And the people seem to have decided already – to politically disrobe the Generals and create a new system where the military is just a cog in the wheel and not the axle supporting the wheel. But, the UN doesn’t seem to be listening. Instead, it continues to hum its favourite lullaby of liberal conflict resolution, according to which achieving quick stability and clearing the way for donor interests remain paramount. If that means preserving the existing sources of violence and subjugation within the country, so be it.

It is this fundamental dissonance between what the Myanmar people want and how the UN operates ideologically that will continue to hamper well-intentioned attempts by the international organisation to “solve” the crisis in Myanmar.