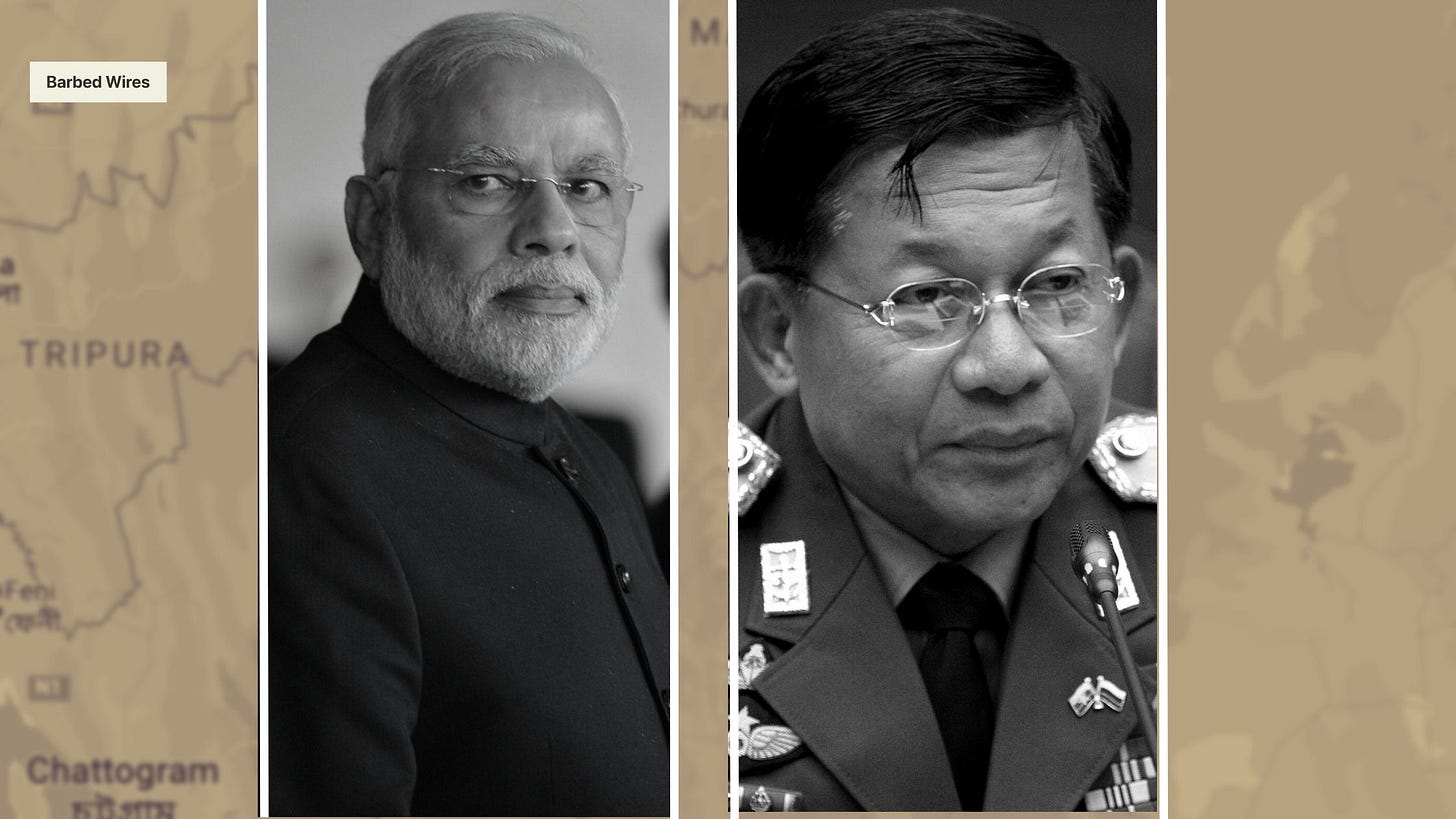

Three Years of Coup in Myanmar: What Explains India’s Pro-Junta Position?

Why won't New Delhi formally engage pro-democracy forces next door?

1 February 2024 marks three years since the military in Myanmar violently dislodged the civilian government, dissolved the parliament, declared a state of emergency, and arrested nearly every prominent political leader, including Nobel laureate, Aung San Suu Kyi.

But, unlike in the past, the people of Myanmar have challenged the 2021 coup with historic defiance, persistence, and organisation. The regime, led by Min Aung Hlaing, today faces the wrath of not just ethnic minorities, who have long opposed the Burmese military-state, but also the ethnic majority – Bamars – from which it once drew political fodder and social legitimacy.

Since October, when three powerful ethnic armed organisations launched coordinated offensives against junta targets in northern Myanmar, the military has struggled to keep its head above the water. It has lost large swathes of territory to revolutionary forces. Entire battalions have surrendered without a fight, the latest one being in Rakhine State. Even its neutral partners and long-time allies, such as pro-talks ethnic armed groups and subordinate border militias, are abandoning the sinking ship that is the “State Administration Council”. Most of all, the top boss himself is facing rising internal opposition.

Not to forget the unfathomable human costs of the putsch: more than 4400 killed, 25,000 arrested, and 2.6 million internally displaced, all since February 2021.

Despite these, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in India continues to formally engage with (only) the junta. It has had conversations with pro-democracy entities since the coup, but these have been no more than informal, below-the-radar, or at times, purely tactical, engagements that haven’t resulted in any policy shift at the highest levels of the government.

One could argue that India continues to formally engage the junta because of its entrenched geopolitical interests in Myanmar. Three key objectives become salient here: securing and stabilising the India-Myanmar border, maintaining and strengthening economic ties, and balancing the Chinese presence.

But, these are inadequate in explaining why New Delhi hasn’t yet formalised its engagement with the democratic forces in Myanmar. In fact, one could even argue that if it was really about fulfilling key strategic objectives and protecting its “national interests”, India should have already engaged the democratic side.

There are three deeper structural and ideological factors that explain the orthodox, pro-junta posture of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government.

Path dependency

One, the Indian political and security establishments are path dependent on working with the Myanmar military.

Since the early 1990s, New Delhi, guided by a strictly realpolitik logic, has abidingly worked with successive military regimes in the country. The end of the Cold War and the opening up of the Indian economy in quick succession created an overwhelming incentive within the Indian foreign policy system to prioritise economic growth and strategic outreach over idealism. The result was a cold, arithmetic mantra – work with whoever is in power in the Burmese capital.

This path dependency became even stronger in the last decade, as the Modi government fortified relations with the Myanmar military. Importantly, it did so despite the democratic transition next door, which brought Aung San Suu Kyi to power in a free-and-fair election. While New Delhi embraced her administration with open arms, its continued to believe that the military wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

In fact, there was a surge in bilateral activity between the defence establishments in New Delhi and Naypyitaw after 2015. High-profile mutual visits of senior def-sec officials, joint counterinsurgency operations along the border, military training exercises, sale of heavy military hardware (such as torpedoes and submarines) – the Modi government really gave it all to invest in Min Aung Hlaing’s military. All of this was designed to fortify the Indian presence at China’s doorsteps and create strategic depth in the Bay of Bengal region.

New Delhi has found it difficult to break out of this path dependency – some would say, overreliance – after the 2021 coup. It is predisposed to believing that the military remains a formidable political force in Myanmar that is facing serious challenges, but will eventually “stabilise” the country like it has in the past.

On Myanmar, there is another legacy impulse to which India remains hostage: working with a prominent civilian leader. New Delhi was very much taken in by Suu Kyi because of her towering global image, undisputed dominance in domestic politics, and past connections with India. The 2021 coup and the multi-ethnic revolution that came in its wake pushed her into oblivion. New Delhi barely recognises the new faces populating the current pro-democracy spectrum, including the senior leadership of the National Unity Government (NUG).

So, suggestions made to New Delhi on talking to the NUG are often returned with a cross-question: whom should we talk to?

It is a different matter that the Modi government hasn’t done enough to familiarise itself with the new generation of leaders, many of them millennials and Gen Z, who are leading the anti-junta front with both grit and sophistication. When the junta falls, which should be soon, it is this leadership that will take charge of Myanmar’s affairs.

Centralisation of decision-making

Two, under the Modi government, decision-making on Myanmar – like on many other fronts – has become overly centralised. In the process, it has become heavily securitised.

A lot rests on a few senior figureheads, among whom the National Security Advisor (NSA), his two deputies, Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), and the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) of the Indian Army’s Eastern Command play critical roles. These offices have always been pivotal in shaping India’s neighbourhood policies. But, the Modi government, through bureaucratic restructuring, has made some of them even more powerful.

It has, for instance, elevated the NSA – Ajit Doval – to cabinet rank, allowing him to call the shots on a host of issues that were earlier outside of his office’s remit. It has also created the CDS’ post from scratch. Although the CDS cannot override decisions taken by individual service chiefs, she/he can informally dismiss their considerations. Since the CDS is the highest-ranking military officer in the system, service chiefs could find it difficult to reject her/his advice. Such a structure risks creating a closed feedback loop.

Sure, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) is also involved in crafting India’s Myanmar policy. But, it seems to be doing little more than delivering soft statements on restoration of democracy and protection of border security, maintaining a diplomatic presence in Yangon, hosting the occasional cultural functions and business conclaves at the embassy, and facilitating secretarial-level engagement with the junta’s senior leadership. All routine, low-stakes activities.

In fact, another ministry appears to be more closely involved in decision-making around Myanmar than the MEA: home.

Only last week, union home minister, Amit Shah, announced that the India-Myanmar border would be sealed and the Free Movement Regime (FMR) scrapped, a move that would effectively bar asylum seekers fleeing the junta’s violence from seeking refuge in India. In August, he linked the crisis in Manipur to Kuki refugees from Myanmar. In October 2022, Shah claimed that “Myanmar citizens” were opening bank accounts in Manipur. Finally, it was his ministry that, just a month after the coup in February 2021, asked border states in the Northeast to stop refugees from coming in (a decision that was later withdrawn).

All of these issues fall within the home ministry’s mandate. But, the tone and manner in which the home minister has iterated them convey a clear message: as far as the dire situation in Myanmar is concerned, New Delhi is only bothered about its security implications on India, rather than the devastating humanitarian consequences on the people of Myanmar. In many ways, this negates the relatively more humanitarian, pro-democracy tone that the MEA has taken in many of its statements.

Moreover, the all-powerful home ministry shares joint control of the Assam Rifles, which guards the India-Myanmar border, with the defence ministry. This allows it to directly shape India’s posture along the border, which is critical to the current situation in Myanmar.

These processes of recalibration of influence and concentration of power have had two net outcomes on India’s Myanmar policy: one, decision-making has tilted towards the defence-and-security, rather than the political, side of things; and two, decision-making has become opaque.

These, in turn, have had three second-order consequences: one, because of the heavily securitised approach, values of democracy, justice and human rights have fallen further down to the bottom of the decision-making pyramid in New Delhi; two, intelligence-level inputs, which often precisely reflect the shifting ground realities next door, are not adding up to commensurate decision-making at the highest levels in the government; and three, the system isn’t absorbing a broad enough set of critical recommendations.

Ideological drivers

Geopolitical interests or even domestic systemic factors don’t adequately answer why India remains a fast friend to the junta in Myanmar. One has to scratch on and dig deeper to identify the core ideas that shape foreign policy.

India after 2014 isn’t the India of yore. The dominant ideological framework of mainstream politics has shifted dramatically. Simply speaking, India, under Modi, has moved towards the right. It has metamorphosed from a secular to a majoritarian, counter-pluralistic democracy. As an inevitable byproduct, authoritarianism has crept into daily political practice. Ethno-religious minorities have found themselves at the sharpest end of this fatal devolution. Critical thought is being discouraged through suppression of dissenting voices, free media, NGOs, and even think-tanks.

Each of these trends and tendencies are equally conspicuous in junta-ruled Myanmar. The military’s style of doing politics – not so much the fact that it is in the business of politics – probably has many silent takers in India. Hindutva provocateurs close to ruling party figures have even directly referenced violence perpetrated by the Burmese army against Rohingya Muslims of Myanmar to rationalise their own sectarian rhetoric. The congruences of political thought and practice are uncanny.

These do not imply that the Modi government’s pro-junta policy is purely driven by ideological overlaps. After all, even supposedly secular Congress governments in the past have worked with military regimes in Myanmar, often looking away from their abuses. It does, however, mean that New Delhi would now likely be even less invested in rooting for democracy in Myanmar, let alone intervening to displace the junta.

But, this goes beyond the Bharatiya Janata Party’s majoritarian political ideology. The hesitation to formally engage the pro-democracy side in Myanmar, which includes several armed groups, is rooted in the Indian state’s own experience of dealing with insurgencies – especially in Northeast India, Kashmir, and central India. In most cases, using brute force and imposing states of exception (such as the Armed Forces Special Powers Act) have been the government’s first response to insurgencies, many of which were explicitly secessionist.

This long history of battling anti-state rebellions has infused a natural revulsion for armed movements in the Indian state’s mind. While pro-democracy armed groups in Myanmar today do not espouse secessionism and largely operate within the ethical bounds of a just war, New Delhi, deep inside, remains suspicious of them. Parts of the current government and defence establishment probably even believe that they deserve to be dealt with force. Going by this, one could argue that India would openly engage Myanmar’s armed groups only when their leaders join the mainstream political fray.

The only major exception to this rule was India’s open support for Mukti Bahini, the armed resistance front that successfully secured Bangladesh’s independence from Pakistan in 1971. In that case, however, India had a specific strategic reason: the imperative to defeat an “enemy state” in its eastern neighbourhood. In Myanmar’s case, New Delhi does not see the entity that the armed groups are fighting – the junta – as its “enemy”. The difference is decisive.

This, then, begs the (rhetorical) question: is India not supporting Myanmar’s armed revolutionary groups simply because it doesn’t want to betray an old friend?

Where is the vishwa mitra?

In his latest book, Why Bharat Matters, Indian foreign minister, S Jaishankar, argues that India today is a “great contributor to solutions, regional or global.”

“This marks its emergence as vishwa mitra, a partner of the world that is making a great difference with each passing year,” he writes. Prime Minister Modi conveyed the same message at a navy event in December.

For those who do not speak or read Hindi, which would cover most of the population in Myanmar, vishwa mitra literally translates to “friend of the world.” One wonders aloud where is that “friend” when a close neighbour that shares a 1640 km-long border with India needs it?

In an interview with NDTV on 31 January, Jaishankar, citing the Modi government’s “Neighbourhood First Policy”, further emphasised that India has developed “real friendships”, rather than transactional relationships, with its neighbours since 2014. Where is that “real friendship” for the people of Myanmar?

The Modi government needs to confront a hard truth: continued friendship with the Burmese junta has harmed India’s interests. The coup has wreaked havoc along the border by pushing refugees into the Northeast, opening up new contraband routes, and causing constant panic among the population living in border areas. Hlaing’s regime continues to consciously harbour anti-India militant groups, some of whom have been adding to the troubles in strife-torn Manipur. India’s key development projects remain stalled and its commercial investments are stuck in a pit.

We have been made to believe that this is an India that will stand up for itself and do everything in its capacity to protect its “national interests.” But, on Myanmar, where India’s core interests stand threatened by an impudent and barbaric military regime, we are yet to see the diplomatic bravado that senior figures in the current government, including the Prime Minister himself, have projected in their public iterations.

Most policy wonks today would call India’s Myanmar policy a case of “strategic restraint.” But, even in the sobering business of geopolitics, there is a fine line beyond which “strategic restraint” starts looking like “strategic indifference.”

How would you see India's Myanmar policy visavi China?